And How can man die better

Than facing fearful odds

For the ashes of his fathers

And the temples of his gods

—Thomas Babington Macaulay, Lays of Ancient RomeI cannot account for when the attack started in our times, but it has become more prominent lately, even though it was predicted in the first century, and proscribed against in the days of Moses. This attack; one against the fifth commandment, the first with a promise: "Honour your father and mother, so shall your days on the earth be long." This command is under attack. And those who most attack it, whose set intersects with those who attack our dear St. Paul, would not condone it if you undermined the commandment, "Do not murder." The slogan of this attack —at least its most common one— is "You don't owe your parents anything."

“Thou shall not murder” justifies itself. Whether by appealing to our self-interest, the pain of losing a loved one, or some other root of sympathy, not many people object to the sixth commandment. For this command, being so self-evident, causes, I believe, some to think it unnecessary to be there to start with. For why would God add something so obvious? Do not our reason and our conscience simply tell us that already? Such is the refrain among the atheistic humanists who believe in objective morality not grounded in a deity

Now some may regard the command “you shall not murder” as overkill, owing to the gravity of the deed. But I perceive it is much easier and much more common to dismiss the command to honour one’s parents. This case, however, owing to its levity. It is a command seemingly so trivial that we might joke that Moses, like a student, intended to fill his essay’s word count. And if he so aimed, surely he was mistaken: we can think without deep brooding, of multiple offences graver than an occasional disrespect of one’s parents. This we think, at first glance.

However, as we walk through the scriptures on other quests, we observe —if our curiosity is even mildly alive—that laws, commands, stipulations, and penalties concerning obeying one's parents or doing otherwise stick out like unbending reeds.

It is impossible to ignore the first command that prescribes our duty to fellow men. For having prescribed our duties to Him, God ordered human affairs. Not by first proscribing theft, adultery, and the grave hurts we might inflict upon one another. He instead commands us to honor parents, a seemingly strange thing to our contemporary moral calculus that plots good and evil by its harm gradient and the consent of the parties involved.

But this merely starts the instance that announces the significance of what still looks to us like a trifle. However, were we to think of the decalogue as a whole, every part fitting into the other in some deliberately arranged manner, we will see the fifth commandment as the bridge between our duties to God and our duties to our fellow men. This way, the decree grows in significance, foreshadowing Paul the apostle’s interpretation as “obey your parents in the Lord,”1 where “in the Lord” signifies authority.

The evidence therefore mounts, from Ham and Noah2 to the parents who cast the first stone at the rebellious child3, that this command is by no means trivial. As the penalty for cursing one’s parents is death4. That parents could give up disobedient children for condemnation. But children could not return the favour to awful parents, allowing them to walk away with the most heinous of crimes. A deed so riveting in the ancient world that Socrates, standing outside the pages of sacred scripture, sat appalled when Euthyphro brought a charge against his truly guilty father, opening up a Socratic inquest on the nature of piety.

Yet if this isn’t enough, we return to scripture to find this honour to parents reinforced; this time by The Lord Himself, with a stern rebuke to the Pharisees: “But ye say, Whosoever shall say to his father or his mother, That wherewith thou mightest have been profited by me is given to God; he shall not honor his father. And ye have made void the word of God because of your tradition.”5

But still, if that doesn’t seal the matter, in places more than one, added to the common signs of the perilous age —sexual degeneracy, hedonism, wars and rumours of war—we get an often passed-over “disobedience to parents”6 as one of the signs of the perilous age. Surely, now, with the evidence stacked before us, we must pause to think, to consider, why before not being a murderer, an adulterer, a thief, a false witness, and a coveter, you must be an honourer of parents. Surely this is a curious matter.

For I suppose not many of us see one who dishonours parents as a degenerate. We know degeneracy of every kind: a murderer we quickly denounce; an adulterer is scum of the earth. The false witness must suffer the penalty he would have brought upon his victim and a thief must pay seven folds. However, the man who turns his back on his parents; who questions the ground of his being; who spits ingratitude, lamenting why his parents had him without his consent is somehow, the enlightened fellow. The liberal thinker. The intellectual who diagnoses the evils in this world as stemming from a “lack of consent.”

This way, what seemed trivial gains some importance before our eyes. A minute ago the fifth commandment appeared as a Mosaic waffle. The next minute we see something God is very serious about; a law with a promise on one end, and the death penalty on the other. And now we are puzzled. What are we missing? We know this thing is somewhat important, we just don’t know why.

We may begin justifying its gravity by returning our gaze to the two tablets housing the decalogue. And if our eyes and minds are keen, we might notice this important distinction. Of the ten commandments, eight are negative laws, while two are positive. Eight of the ten commandments restrain, telling us what we must not do. But two successive ones —the Sabbath law and the law now being treated—tell us what we must do. So begins our understanding of the command to “honour your father and mother.”

Were we to rewrite the command in the spirit of negative law, this would have been the composition: “you shall not dishonour your father and mother; nor shall you curse them.” This way, the fifth law would have resembled the other eight and would have been —so to speak—common sense. However, this was not so. For I believe that the positive declaration of the fifth commandment was deliberate. Deliberate to achieve other ends than meets the shallow eye. For one remains guiltless before the law by restraining from murder, theft, adultery, coveting, and perjury. But no one remains guiltless by simply not dishonouring parents. ‘Not dishonouring,’ we might say, does not amount to honour. Or to put it another way, fulfilling the fifth commandment is not a matter of restraint, but a matter of performing. You fulfill the law, not by inaction, but by action. Thus we see, as the first feature evidenced in our investigation, that this command is first and foremost a duty.

Proceeding then in light of this, or perhaps looking back in time, to the instance of Noah’s drunkenness and his sons’ reaction, honour as duty leaps out to us: Ham did nothing positive, content to look on and tell his brothers. His brothers, Shem and Japheth, acted otherwise; first declining to look upon their father’s shame and covering it up simultaneously.

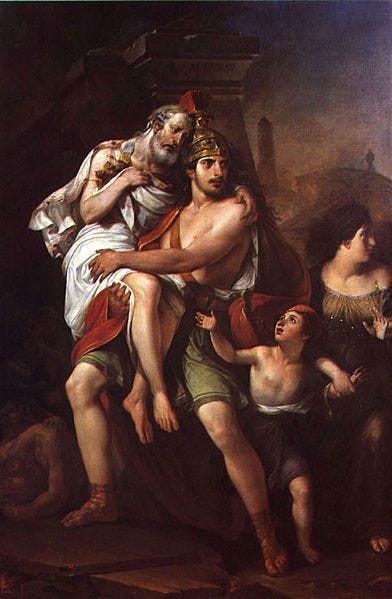

Honour as filial duty is, however, in the broader Western world, best captured in Aeneas as narrated by Virgil, carrying his weak father Anchises on his back as they fled Troy consequent to its sacking. Virgil writes thus, Aeneas speaking:

Come then, dear father, clasp my neck: I will

carry you on my shoulders: that task won’t weigh on me.

Whatever may happen, it will be for us both, the same shared risk,

and the same salvation (Bk 2:707-710)This act —of carrying his father on his back—makes Aeneas into a godlike figure, who the founders of Rome eagerly claim as their ancestor. Aeneas was already a respected fellow in Ilios, even beloved by the gods, Venus saving him once from Diomedes’ unstoppable fury. But his (Aeneas’) heroism on the battlefield dims beside his deed of fleeing the fallen Troy with his father on his back, his son by his side, and their gods with them. This reverence for Aeneas’ deed lets us know something of ancient sensibilities.

Sensibilities further established by looking at the Olympic games in Ancient Greece. These games were, as Pindar’s Odes shows, not for personal glory. Rather they were a form of honour the athlete paid to his family and city-state. Just as victorious national teams in International sports events today bring glory to their countries. In other words, all the labour and discipline that an athlete undertook to emerge victorious in a contest were intended less to bring glory to himself. No, he aimed —ideally—to bring honour and glory to his home. Perhaps this is why one’s ancestry takes an important place in the ancient world —warriors, heroes, and kings are introduced per their lineage, telling whose son they are. This is at once humbling and exalting for the heroes: they are reminded that they did not come from nothing as though they are immortal, and in case they belong to a noble lineage, it challenges them to strive for honour. “Do not forget the son of who you are” taken literally.

To buttress this sense of honour as a duty; a deed rather than abstinence from its antithesis, we may refer one more time to Christ’s rebuke of the Pharisees: “But ye say, Whosoever shall say to his father or his mother, That wherewith thou mightest have been profited by me is given to God; he shall not honor his father. And ye have made void the word of God because of your tradition.” Christ rebukes the Pharisees, not because they teach the people to actively dishonour their parents. But by teaching people to withhold gifts due to parents, redirecting it as an “offering to God,” they ensure people don’t actively honour their parents, making void the Word of God.

We might investigate ways we ought to honour parents. But I will leave it to the reader to apply himself. But I will have you remember this. That in our earthly pursuits, when we say we wish to honour a person's memory, we do something; perhaps set up a memorial, a foundation, something that immortalises them. Therefore, honour is a deed. So, in the Greek athlete who brings glory to his ancestry and his city-state; like the father-carrying Aeneas; like the father-covering Shem and Japheth, we see the essence of the fifth commandment typified—there is no fifth commandment without a deed.

Having worked that out, it still does not immediately disclose its importance. We have known its character but we still stand short of realising its significance. To draw a contrast between this command within our scope with the others, we can quickly infer the import of the prohibitions to murder, adultery, theft, covetousness and perjury. It is quite self-evident what these laws afford us. Or what their absence cost us. I shall not belabour the reader with how dastardly our societies will be if we declared a 24-hour, purge; where all laws are suspended and no crime and sin ‘exists.’ Such a society will implode that develops no measure to address murder, concupiscence, theft, greed, and perjury.

However, with the fifth commandment it is not so. It is not evident that we know what this duty fulfills. Nor do we know what shirking it cost us. Not many times have we diagnosed our social ills with a statement as this: “This is a product of not honouring your father and mother.” In metaphorical terms, we might ask, “What really was Ham’s sin? Don’t you think Noah overreacted?” Of Aeneas and Anchises, the sentiment might be more mellow. Yet we may probe thus; “Why was escaping with Old Anchises Aeneas’ most heroic act?” All this to say that this command, across all layers of analysis, proves that its importance is enigmatic. Which is why the attack on it fails to alarm us. The fifth commandment has had to endure the onslaught of a consent-based morality; a morality that honours only the obligations it chooses; an egotistic morality that does not admit the right to things not of its own contriving. In short, an impious morality.

For the fifth commandment, in all our analysis thus far, is what the ancients and some wise moderns have called by the term pietas. An admittedly vague term which means everything —and by consequence nothing. Which being so hard to present in pure ratiocination, writers have resorted to myths and narratives like those of Aeneas to show rather than tell what concept this pietas is.

Therefore, to call something impious is to say it departs from piety (an impoverished English translation of the term). Yet for all its popular association with religious emotion and submission, piety strikes farther than the boundaries of religious feeling. As such, John Dryden offers one of the most encompassing definitions of piety thus: “Piety alone comprehends the whole duty of man towards the gods, towards his country, and towards his relations.”

And at once you see, retrospectively of course: the Greek athlete performs a duty to his family, ancestry, city-state, and earns praise for the gods. Aeneas not only carries Anchises on his back, but also his son Ascanius by his hand, his wife Creusa following behind, and the servants of their household. When his wife was lost, Aeneas went back into the burning city to find her, only relinquishing the mission when Creusa's ghost forced him to look ahead rather than behind. Returning thence from this failed quest, the refugees from Troy were waiting for him to lead them to a new land:

And here, amazed, I found that a great number of new

companions had streamed in, women and men,

a crowd gathering for exile, a wretched throng.

They had come from all sides, ready, with courage and wealth,

for whatever land I wished to lead them to, across the seas.

(Aeneid Bk 2:)What was a decision to honour his father and save his family, became for Aeneas, the beginning of a new and glorious future and the mythos of Rome.

And finally, we see Ham, through his shameful undeed, bring a curse on Canaan —a curse we often think went on Ham himself:

Cursed be Canaan

The lowest of slaves

he will be to his brothers.

(Genesis 9:25)While it is hard to tell precisely how Canaan came into the picture and received a curse on the basis of his father’s actions, we cannot wave away that such was the case and is instructive. Contra Aeneas, one act of dishonour towards his Patriarch —that is by Ham—spelt endless troubles for Canaan and his descendants up until the time I write this.

Thus we see fitting through Dryden’s lens, the far-reaching power of pietas and by consequence, the fifth commandment to honour one’s parents. For pietas is the core and essence of the fifth commandment —ontologically speaking. Through pietas, we not only honour —or do duty —to parents. But to God, and other relations.

So we see encapsulated in this one law, as I presented at the beginning, the opening up of our duties to our neighbours. The command to “love your neighbour as yourself” opens with the duty to honour your father and mother. But within it, and the consequences of it, just as we see in the promise that “so that your days will be long in the land,” we see that its benefits are great. That the fifth command does not find itself in such a rank by mistake. That it is there by God's deliberation. That once God had emphasized our duty towards Him, He commanded us to do duty to parents. In short, it is no trivial command.

Why then does our modern age take it trivially? Why does our consent-based morality sustain its attack by insisting that because we did not ask to be born by these parents, we owe them nothing?

Now there are some and many among us who retain good sense and good sentiments: they argue that we who have good parents do owe them some due; a due which we better call “recompense” —recompense for all their efforts. But this merely establishes a contract; a more kindly quid pro quo better than the pitbull rabidity of the entirely disruptive kind that characterises the age.

However, the fifth command makes no provision for this type of contract. It never prescribes your duty to your parents based on their goodness. It casts an absolute blanket. And it contrasts itself with other types of honour in the Bible. Like the honour to be given to exemplary Elder and overseers who we honour for their work sake. We have not received the command to honour fathers and mothers because of their stellar parenting record. Once more, we see what feels like an unearned privilege by the simple fact of procreation —remember that parents could bring children for judgment but children could not do otherwise. Remember Euthyphro.

Perhaps then this privilege is what makes the command repulsive to a moral matrix that has only consent, contracts, and self-interest. It is a matrix that wishes to determine, wholly and absolutely, the terms of the contracts. It wants to determine how and when it will do good. It denies, according to Richard Weaver, “any source of right ordering outside itself.” It wishes to reward only those who it judges as good; that is, anachronistically. And to punish those forebears it judges as evil —also anachronistically. Therefore Richard Weaver maintains that “modern man is a parricide. He has taken up arms against, and he has effectually slain, what former men have regarded with filial veneration. He has not been conscious of crime but has, on the contrary, regarded his action as a proof of virtue.”

This parricide manifests itself as a denigration of tradition. Of ancient wisdom and landmarks. If we ever meant anything by “modern,” it is that sharp break away from what came before. This is parricide by negligence. For by ignoring one’s forebears, one fails to do right by them, which automatically contravenes the positive command to honour —to “do duty” towards one’s parents. But here ‘parents’ represents all that came before and played a role in your being here. However, the Bible does not take kindly to not giving one’s ears to his parent’s instructions. The command is clear: “obey your parents as God’s authority”; “My son, keep your father's commandment, and forsake not your mother's teaching.”7

In this way, piety is a prescient measure given by God, flowing from His character, against the tempestuous impiety that is common to man. If it was not a problem it would not have been commanded. Therefore we see the effect of the disobedience to this command pour out in all sorts of vices. “The Spirit of Modern impiety” Richard Weaver again says, “would inter their memory (of heroes and martyrs) with their bones and hope to create a new world out of goodwill and ignorance.”

The effect of this? “Modern civilisation, having lost all sense of obligation, is brought up against the fact that it does not know what is due to anything; consequently its affirmations grow feebler,” Richard Weaver declares. And this is how the living disenfranchises their ancestry. By denying their wholesome traditions. For tradition, Chesterton famously defines, is “an extension of the franchise. Tradition means giving votes to the most obscure of all classes, our ancestors. It is the democracy of the dead.” But through impiety, and foolish presentism, the progressive mind counts parents —both living and dead—as irrelevant relics of a time eschewed.

To look upon everyone who came before as not knowing better than us, because, “we are the most advanced of the species,” is to not keep your father’s commandments and forsake your mother’s teaching.

Going by this, it is no wonder that through the loss of all filial sentiments; seeing ourselves at once as the ground of our being and author of our fate, that those who spurn their ancestors, caring only for themselves, do not also care for their descendants. Those who by all means avoid empathising with their parents, even for the sake of knowing where they got it wrong, cannot be the best parents to their own offspring —that is if they get to be parents at all.

By being ensconced totally and wholly in the present, we have reached a world record affection for antinatalism, lamenting the distress of this world and real as well as imminent danger. We have ideologised ourselves into infertility and barrenness. Having squandered the economic resources and cut down trees that would have been shades for the unborn, we ensure that we drive down genuine erotic desire crucial for reproductive flourishing.

Remembering again Dryden, that piety comprehends the whole duty of man towards the gods, towards his country, and towards his relations, Richard Weaver observes that

“It is inevitable that the decay of sentiment would be accompanied by a deterioration of human relationships, both those of the family and those of friendly associations, because the passion for immediacy concentrates upon the presently advantageous. After all, there is nothing but sentiment to bind us to the very old or to the very young. Burke saw this point when he said that those who have no concern for their ancestors will, by simple application of the same rule, have none for their descendants.”

Is this —the deterioration of human relationships—not true of us today? With our boasts of consent, we have managed to be the loneliest generation to have ever lived; notwithstanding all the communication technology we have brought to life. Just as dying societies accumulate laws like dying men accumulate remedies, we accumulate relationship advice of all types and form because we are lonely, contra the delusion that we know the schema of relationships better than our ancestors.

Every Instagrammer has a few words to say on love and being intentional. And secrets to friendships. And secrets to keeping boundaries. And so on. But this is merely hospice for a frigidly cold society that has lost all the fire and warmness of genuine relationships. All through impiety. For by refusing to submit ourselves to the obligations we did not choose, we lost the discipline of the will that is the crucial importance of the fifth command of Moses’ decalogue.

One must humbly realise at this point that mathematically worked out consent does not and cannot ground human relations. We are all actors arriving in an eternal drama. It is stupid to begin rewriting the script upon our entrance. One must submit to obligations of piety, obligations that, Roger Scruton writes, “have never been undertaken but which are owed to others in recognition of their entitlement, or in gratitude for their protection, or simply as a humble acknowledgment that we are not the authors of our fate.”

Surely we can accept that we neither originate ourselves nor can we author all our events. Chesterton wrote thus:

“But in order that life should be a story or romance to us, it is necessary that a great part of it, at any rate, should be settled for us without our permission… A man has control over many things in his life; he has control over enough things to be the hero of a novel. But if he had control over everything, there would be so much hero that there would be no novel…The thing which keeps life romantic and full of fiery possibilities is the existence of these great plain limitations which force all of us to meet the things we do not like or do not expect.”

If we can accept that we neither originate nor author our fate, it is wise that we strive to submit to the prescribed obligations we have not chosen by acutely reasoned self-interest. For piety, according to Roger Scruton, “is a posture of submission and obedience towards authorities that you have never chosen. The obligations of piety, unlike the obligations of contract, do not arise from the consent to be bound by them. They arise from the ontological predicament of the individual.” As such we reach a crucial point: an invitation to see the second-order consequences of “submission and obedience towards authorities that you have never chosen.”

Consider that the ego is a wild thing. And rebellious. And foolish. So it requires training and ruling to not so much as tame it, but nurture it rightly. Because this ego, if left alone, because it is passionate, would run wild and burn the world like the Samson’s foxes in the Philistines’ field. What measure do we suppose God has prescribed for the wild ways of the ego? If we are inclined, quite naturally towards impiety, what is God’s remedy even before we knew it?

If through impiety we ruin all familial and human bonds, through piety we may restore them. Therefore in observing piety’s operation, we observe with Richard Weaver that “Piety is a discipline of the will through respect. It admits the right to exist of things larger than the ego, of things different from the ego.” That is through piety —through honouring father and mother—we bridle the ego and make ourselves realise that this duty towards those who came before us or through whom we came is not something we have chosen. It may sting. But it does so for a moment. Just before the flush of healing sentiments pour out on our souls and flows to heal our entire social fabric.

But it doesn’t flow sideways alone; to our human fellows alone. But upwards as well. To God also. For we know that our ego's greatest rebellion is the rebellion against God. God is quite often the last person we choose. Surely because we cannot consent to Him. In fact we hate Him, being dead in our sins. Alas He Himself has said, “ You did not choose me, but I chose you.”8 Therefore we reject Him who we cannot choose. Our souls, because of our throbbing ego, become increasingly inclined away from our maker—the one true ground of all being out of which arises the ontological predicament of every individual.

So the pieces start to fit. A rabidly atheistic age also rejects parentage. And the rebellion against parentage is only an earthly rehearsal of rejecting God. Now Apostle Paul makes sense all over again in his various teachings that children should obey their parents “in the Lord” or “as God’s authority.” We see now the pulse of his warnings about disobedience to parents being a perennial warning sign of the perilous age. Certainly we see why “honour your father and mother so that your days will be long” bridges the first four commandments with the five that follow after it.

For the fifth commandment in fact orients the mind towards God. It disciplines the will through respect towards accepting superior beings who not only precede us, but who are themselves our source. Those who honour parents gain the disposition; the mental and spiritual posture and inclination to honour God. Honouring one’s parents becomes both a rehearsal and consequence of honouring God. The one feeding back into the other Which all directly opposes the progressive orientation that sneers at what comes prior, dismisses it, and is ungrateful for it. It is therefore no surprise that the most obvious symptom of progressivism is the desire to stand between parent and child; to institute a cult of youth and inaugurate struggle sessions where children may lead the mob that persecutes their parents all in the name of ideological correctness.

As John the Apostle said, “If anyone says, “I love God,” and hates his brother, he is a liar; for he who does not love his brother whom he has seen cannot love God whom he has not seen.”9 In the same vein, no one can claim to honour God and not honour his father and mother (however broad you might apply this appellation). For all our labours, we can conclude here the import of this great command.

Yet, in one last effort, we might endeavour to look down or sideways to our fellow man. To let our gaze, with God filling our hearts, observe the moral content pietas pours out to our neighbour.

This is obvious isn’t it? A man whose will has been disciplined through respect will not murder his neighbour. He will heed his father’s advice and avoid Adulteress Express. He will not steal and against all odds he will temper himself from committing perjury. He will check himself and find within him the will to restrain his coveting appetite. Why won’t his days on earth be long? Barring any other misfortune he will not be a murderer liable to lose his own life. By avoiding adultery he will avoid the fury of an angry husband; he would avoid carrying hot coals in his bosom. These are practical considerations —considerations which I suppose no longer now look to us as Mosaic trifles.

But a man lacking a disciplined will does not know where he will find himself. He will surrender to every temper —internal and external.10 Making decisions that threaten his life and longevity in the land. A man with a ruptured will will live less like a man; he might even start looking like a beast. We must not envy him. We must not admire him as enlightened. For the Holy scriptures says11

“There are those who curse their fathers

and do not bless their mothers;

those who are pure in their own eyes

and yet are not cleansed of their filth;

those whose eyes are ever so haughty,

whose glances are so disdainful;

those whose teeth are swords

and whose jaws are set with knives

to devour the poor from the earth

and the needy from among mankindHowever, a pious man not only benefits himself. He also benefits his people. Like the Greek athlete who brings glory to his city-state; like Aeneas who soothes his sacked people and brought them into new land; like Shem who set his lineage up to produce the Messiah, the man with pietas carries blessings bigger than himself; he situates a covenant that outlives him. This way, quite figuratively, even after his passing, his days are truly long on the earth.

Ephesians 6:1

Genesis 9:18-29

Deuteronomy 21:18-21

Exodus 21:17, Leviticus 20:9, Deuteronomy 27:16, Proverbs 20:20

Matthew 15:5-7

Romans 1:28-31, 2 Timothy 3:1-5, Mark 13:12

Proverbs 3:1-2; Proverbs 6:20; Proverbs 13:1; Ephesians 6:1-3; Colossians 3:20

John 15:16

1 John 4:20

Proverbs 5

Proverbs 30:11

Failed to render LaTeX expression — no expression found

Good read

Powerful words